Running more prevents injuries. Assuming that you don’t get injured. There’s no such thing as an overuse injury, they’re under-preparation injuries. We all know that we’re supposed to slowly increase our training in order to avoid injury. That’s both true on its face and demonstrated by significant amounts of scientific research. But why? What’s actually going on inside those bones, joints, and muscles. They’re being remodeled by the stresses to make them more springy and resilient, every single run.

Today, we’ll focus on how a specific part of your tendons respond to chronic running and why stressing them the right way will strengthen them. First, a dive into the science, then some exercise and techniques to make and keep tendons strong. It’s going to get technical, so hang on tight.

What is a tendon?

A tendon is both an incredibly tasty addition to a good bowl of pho and the connection between muscles and bones. Fun facts aside, let’s look at the serious role tendons play in movement. They anchor muscles to bone, allowing the muscle to provide its joint-moving power. The tendon we’re probably most familiar with and most easily palpable is the Achilles. It isn’t just a convenient place to grab your godlike child while you dip them in the River Styx to give them invulnerability, it’s also the connection between your gastrocnemius and soleus complex (AKA calf muscles) and your calcaneus (AKA heel bone) that allows you to run, jump, walk, and basically do everything you need to do. Go ahead, poke yours, I know you want to. Every muscle has a tendon that it attaches to, otherwise the muscle couldn’t do anything, and there are about 600 tendons in your body.

Tendons are made up of three main sections, the myotendinous junction, the main tendon body, and the enthesis, which attaches the tendon to the bone. Each is designed differently in order to allow it to provide its function. The myotendinous junction connects the muscle to the tendon and so contains aspects of both as they fade into each other (and is really complicated), the tendon body is pure tendon, while the enthesis is really complicated as well. Basically, tendons are complicated, but complication is good! It’s interesting and you want to learn about it, I know you do.

Today, we’re going to focus on the myotendinous junction (AKA MTJ) because it’s the most commonly injured part of the tendon complex. The MTJ is that connection between muscle and tendon and the spot where the muscle most commonly gets strained. Let’s talk about why by digging into the science and design of these tendons.

The MTJ Anatomy

This is the area most commonly injured in muscle strains. The MTJ is a fragile part of the muscle because it’s a merging of muscle and tendon tissue. Without diving too deeply into either collagen or muscle anatomy (yet), we can basically say that collagen folds into the muscle tissue here, grabbing on to the different muscle fibers to make a firm junction. Kinda like weaving two phone books together page by page, this interwoven connection makes it incredibly strong. It also raises some risk of strain, as the area has fewer muscle and tendon fibers doing the same amount of work to hold tension as the ones in bulkier areas.

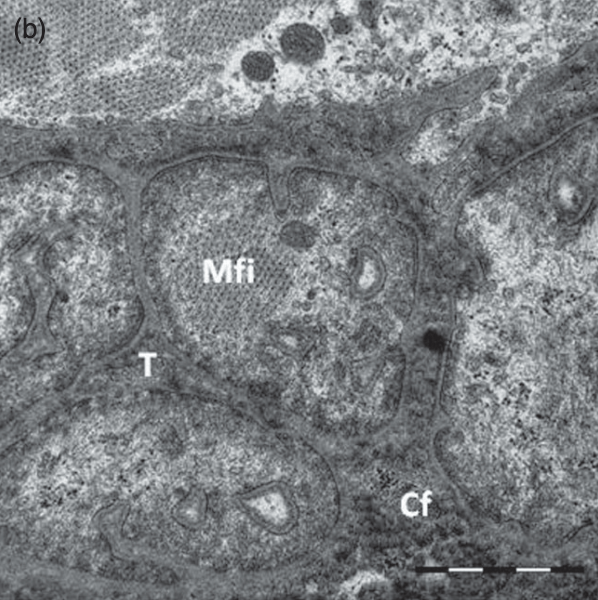

This image shows what’s going on deep inside the tendon, with muscle fibers being completely wrapped up by collagen fibers as they interweave. Usually, muscle fibers are wrapped by the endomysium, a specialized tissue that provides support and nutrition to the fibers. But at the junction, collagen provides the external wrap. In the picture below, “T” is tendon, “Mfi” is muscle fiber, and “Cf” is collagen fiber. It’s amazing to see muscle fibers directly wrapped in this woven collagen, providing an incredible junction between the two tissue types.

The image is from this excellent paper: The human myotendinous junction: An ultrastructural and 3D analysis study

Here’s another image, much more zoomed out, that shows the interface between the dark muscle “M” and the light colored tendon “T”.

Image 2 is from this awesome paper: The Myotendinous Junction—A Vulnerable Companion in Sports. A Narrative Review

Do you see how the tendon doesn’t just stop at the muscle, but weaves itself in? You may be familiar with this from eating meat too, some parts of a pork butt, for example, contain these ends of a tendon and they tend to be the tougher area because tendons are a much tougher texture than muscle. In the photo above, see how those little white invaginations slip through the muscle, especially on the right side of the muscle tissue? That transition from tendon to muscle is key to transitioning force from muscle to tendon to bone. It’s also an area where there is less muscle structure, which is what makes it more prone to strain.

And while I’m geeking out over these awesome images, I know that you’re wondering why they matter for running. Well, we know a couple of things about this junction that are important for runners and the tissue remodeling that comes from exercise.

How the MTJ Gets Injured

The first thing we know is the bad: periods of weightlessness or bedridden time can reduce the amount of muscle-tendon infolding at the end of a tendon. This has been studied in both rats and humans sent into space, so we’re rather confident about it. Any unloading of the myotendinous junction leads to less infolding, even if it’s not as extreme as space travel. We’ve even seen this in elite level soccer players. When they’re returning from injury, players who practiced fewer than 10 times since their injury were much more likely to get reinjured in their first match. Every practice session they attended reduced injury risk odds by 7%. So even in elite athletes, periods of unloading can lead to decreased muscle-tendon invaginations and more muscle and tendon injuries. The fewer pieces that are holding the junction together, the easier it is to tear apart.

So that’s what happens when they get detrained. Bad things. But what about when they’re trained?

For that, we need to zoom in a tiny bit more. The tissue that actually fuses tendon to muscle is called integrin. It’s a little protein that sticks out of muscle tissue and grabs onto tendon. Specifically, the integrin that does this is type α7β1, but I’m just going to call it integrin. Other proteins involved are vinculin and talin, they also provide binding to the muscle fiber skeletons. To save on complexity, I won’t go into details about each individual one of these, but just focus on these binding proteins as a whole. Together, they provide the actual molecular anchoring of the tendons and muscles together. They grab onto one another, holding the muscle and tendon cells tightly together. So the more of them you have, the better anchored the area will be, and the less likely to strain.

This is a good time for a note that’s key to all of this. Things in the body don’t just “happen”. They’re based on specific molecular interactions. Literally every single thing your body does is based on how the molecules in it are interacting with one another. That’s why we’re zooming in so deeply on molecules.

How to Protect a Tendon – Tissue Remodeling

We know a few things about these molecules based on both rat and human studies. Namely this: muscles and tendons make more of them after exercise. They make even more of them after running exercise and make even more of them after eccentric exercise. Eccentrics are exercises where the muscle lengthens while contracting. Like slowly lowering a weight. You’re using the muscle while it’s getting longer. The most common hamstring exercise like this is Nordic Hamstrings, a hugely recommended exercise when returning from hamstring strain.

So the more you exercise, the more molecules you’ll have linking your muscles and tendons together. This prevents things like muscle strains and tendinopathies and is the reason why more training leads to fewer injuries. You’re creating more anchor points between the muscles and tendons, interweaving them more, and making that junction stronger, with every run you do.

The myotendinous junction has to absorb and transmit force in both directions, both up from the ground, to act as a spring, coiling, waiting for the next stride, and down from the muscle, providing push-off and explosivity off the ground. The stronger this junction is, the better it will be able to absorb and transmit those forces with each stride. In a 60 minute run, your muscles will absorb and transmit forces around 5,000 times each, so the more protected they can be against these forces, the better they’ll resist injury.

How to strengthen your tendons – A routine

The easiest way to strengthen a tendon is just by running on it. Research shows that running more will increase the MTJ strength, preventing strain injuries. But there are ways to strengthen them more directly.

We know that eccentric exercise is the best way to increase the amount of integrin, talin, and vinculin produced (and thus strengthen the MTJ), so doing eccentric exercise as part of your regular gym routine is best. The most common tendon injuries for runners are at the Achilles, Glute Medius, and Hamstring, so I’ve collected exercises for each of them below for you to add to your routine. They just take a few minutes per week and will help remodel your tendons to prevent tendinous injury in the future.

First off, Achilles eccentrics:

Then, Gluteus Medius:

And, lastly, Hamstrings:

Adding just a couple of these exercises to your program per week can increase tissue remodeling and massively decrease your tendon injury risk. You’ll add more proteins to your myotendinous junctions, helping them grip more tightly and respond better to the power you’re putting into them.

If you have any questions, leave a comment and I’ll happily answer them. I know this was some deep stuff, so I’m happy to elucidate anything else you’d like. Happy running!

Leave a comment